The following interview is from an issue of the newly defunct magazine Manga Erotics F a little over a year old, a few months after Blade of the Immortal ended. Samura also started a new manga series in the same Erotics F issue: Harukaze no Sunegurachika (“Snegurochka of the Spring Wind”), a single-volume story set in the Soviet Union that goes on sale in Japan in July, and which they refer to in the interview.

So, are you ready to see Samura say some strange, sometimes troubling things about the fairer sex? Great! Here we go:

–Your history as a manga artist has been discussed elsewhere quite a few times already, so this time I want to stick to a narrower, more specific theme—girls. So, first, let’s talk about how you do women in your manga. Visually speaking, what is it you pay attention to when you’re drawing a woman?

Samura: Hmm, well… They sort of tend to come out unhappy-looking when I just draw them naturally. For some reason I just can’t draw a really happy girl. (laugh) Another thing is, I don’t really know how to do voluptuous, so I’m always trying to make them pretty, because that’s all I know. When I’m drawing their arms or legs or whatever, I’m really not thinking about making them sexual at all—I’m always thinking about making them look as pretty as possible.

–Beauty of form.

Samura: Right. I’ve been told by one of my readers that he thought the artist behind my manga must be a woman, because men draw their fetishes into the work more when they draw women, emphasizing certain parts and all that. I hadn’t really thought about it like that. I don’t really fetishize specific parts of the body in that way — I’m always thinking about the balance of the whole.

Men will look at pin-ups and say how the legs are sexy or whatever, but I can’t really relate to that. (laugh) I might think a woman is pretty, or, like, I’ll appreciate their beauty on an aesthetic level, but I don’t really feel sexually attracted to them in that way. Which is why my male readers might feel the women I draw are a bit lacking.

–So you’re not looking at their breasts or butts, but their whole bodies?

Samura: I look at their whole bodies, but I especially like the plain parts of their bodies, by which I mean things like the napes of their necks, the indent of their collar bones, the area around their ribs and abs — places with that smooth shading to them are, I think, just beautiful. Seeing a woman’s nipples and pubic hair actually ruins it for me. (laugh) I don’t want to see that stuff — for me it’s all about things like the shape of upper arms seen from behind, or the shape of the knees. That’s what does it for me.

–You almost sound like a sculptor.

Samura: Because I’m focused on the overall balance. I can see that. This is why my woman characters all have more or less the same size breasts — I can’t draw them really big or really small. I just draw them according to what I think would look best on a character of that age. I consider it a bad habit of mine. (laugh)

–Naoki Yamamoto isn’t picky like that — tiny or huge, it’s all good.

Samura: The man is a master. (laugh)

–When he’s putting his work together into tankobon form, he’ll tell me, “I made the breasts bigger!”

Samura: (laugh)

–So, the balance always comes first for you?

Samura: Making them big just totally ruins the balance for me, always. I’m more into the shading of bones sticking out of skin rather than voluptuousness, so I guess I’m just not capable of drawing big asses or boobs.

–You can really feel the beauty of their figures in your work. So you don’t buy photo collections of female models or anything, then?

Samura: Oh, I do sometimes. I like photos where they’re wearing traditional clothing, and you can see glimpses of their skin, or the clothes are coming undone. It’s a totally asexual thing for me though.

–Have you always been like that?

Samura: I guess so. What I find arousing are things like voices, facial expressions, situations. I can only ever see bodies from an aesthetic perspective.

–Would you say you see it as an almost sacred thing?

Samura: Something like that, maybe. I look at it structurally, almost like a sculpture.

–So when you say that it’s voices and facial expressions and situations that you find erotic, are there specific things that you like?

Samura: There are, but this conversation is going to get dirty.

–Without going into too much detail, please.

Samura: With voices, for example, if you have someone with a really calm, dreary voice, and then she’s surprised or somehow stimulated by something, and that heightened emotion causes her to let out a voice that’s highpitched for a moment — I really like that kind of thing.

–(laugh) Moving onto the next one, then: how about facial expressions? Are the facial expressions you like the ones they make when in pain, too?

Samura: I do draw women in pain pretty much for the sheer eroticism of it.

–I suspect that might have something to do with why your women come out looking unhappy.

Samura: You think? I find weary and frayed much more attractive than happy.

–So in terms of Blade of the Immortal, you’re not a Rin man…

Samura: I’m a Makie man.

–Thought as much.

Samura: That feeling that she’s just given up on everything. This is why I’m not really attracted to young girls. There are a lot of little girls in Bradherley no Basha, but I’m not actually drawn to them sexually — although when their clothes are taken off, there’s their still undeveloped bodies, and there’s something painful about seeing that that I like. So while I’m interested in seeing that, I don’t actually feel a desire to have sex with them or anything. Not sure how to put it.

–We are still talking about drawing this stuff, as an artist… right?

Samura: Oh, yes, I suppose we are. I do try to be a good boy. (laugh) I might feel a sexual attraction to this stuff, but I try to work it off through putting it on the page instead of actually physically acting it out. It’s not that I’m drawing what I want to do to some poor girl — it’s more like I’m trying to record this stuff.

–Trying to “record” it. I see.

Samura: I think so, anyway… But then, I generally think that men who perform that sort of crime on minors should go crawl in a hole and die.

–Fiction and non-fiction are two completely different things.

Samura: Right. What I’d like to tell someone upset after reading Bradherley no Basha is, I need you to allow me to do this stuff because it’s fiction. Authors separate fiction from reality even more than people realize. The stuff drawn in there isn’t some sort of desire of mine, and it’s not supposed to inspire anyone out in the world to do anything like that. I have unfortunate things happen to my characters when the story calls for it.

–True. Will the protagonist in this new manga of yours have unfortunate things happen to her?

Samura: I think so. I didn’t start by deciding I wanted a young girl character and then create a story based around that; I made her that age because that’s what the story called for. The same goes for Bradherley.

–Meanwhile, the series you’re doing in Nemesis has got some really badass women in it.

Samura: If I go and make a female protagonist without setting some sort of specific task for myself, she’ll come out like the ones in Beageruta. The sex they have is by their own volition, and while they may be unhappy, they still manage to stay pretty tough. A long time ago, when Sabe was still alive, I went to his home to hang out. He had this story in one of his books — I think it might’ve been in Shotaiken Hakusho – where there’s this girl who’s being pressured into sex by the boy she likes, and she’s not sure what to do, and her older sister comes home absolutely stinking drunk and starts going on like, “God, I’m so jealous, you guys are living in the best part of your lives! And he’s so hot!”, and the younger sister is like, “You always get led on by bad guys!” and the drunk older sister goes on celebrating them, urging them on. What I told Sabe after reading it is, ”I want to make this older sister happy.”

–What a nice story.

Samura: The kind of character who doesn’t have much luck, but still stays strong and goes on living without whining about it. Someone struggling with things, but who has managed to come to terms with that misfortune. That’s probably the sort of heroine that would come to me naturally. The kind who seems independent, but is actually just barely holding back an intense dependency. There’s something about that that I like. (laugh)

–She’s not actually independent, just holding back her dependence.

Samura: Yeah. She knows she won’t be any good if she lets herself be carried away by a man.

–Like Akagi in Ohikkoshi.

Samura: Like Akagi, exactly. (laugh) She seems strong, but she’s got that side to her.

–And that’s why she needs to keep from depending on people. Maybe it’s easier to draw these strong characters as women, because a girl can’t be as independent as an adult.

Samura: Ah, that’s true. But, there’s also that I’m a grown man who’s not very good for much aside from drawing manga, so if I’m to be in a relationship with someone, she couldn’t be too reliant on me. So maybe what’s happening is that the qualities I personally look for in a woman are coming out in my manga. As sad as that sounds. (laugh)

–I see. You know, there are a lot of men out there who think that women are supposed to depend on men.

Samura: I would’ve loved to have grown up to be one of those men, but I just didn’t. (laugh) It’s a manly thing to say. The sort of female character who likes that sort of man is something I just can’t make work, though.

Samura: I believe in female supremacism. On some fundamental level I am just not as good as women. When I was going to art prep school, the most talented artist there was a girl. Immediately I thought, Holy crap, she’s good. I admired her. After I became a manga artist, the masters I’ve learned under have always been women. I basically grew up on Rumiko Takahashi, see.

–That’s a key point, I take it.

Samura: After that, I read Kei Ichinoseki’s work, and I really wanted to draw like her. And then there’s the fact that I think that Fumiko Takano is the single most talented artist in the manga world.

–Rumiko Takahashi, Kei Ichinoseki, Fumiko Takano – your Holy Trinity.

Samura: Exactly. The people I consider to be the very top turned out to be all women.

–Could you tell me more about what exactly is amazing to you about this Holy Trinity?

Samura: The reasons I think Rumiko Takahashi is great are the same reasons everyone thinks she’s great. The best part is her sense for language. It’s since become so ubiquitous that people looking at her manga now might not know how incredible it was for its time. The almost rakugo-like ways of speaking. She’s who I first learned about the importance of a manga’s pacing from. As for Kei Ichinoseki, she’s got this incredible camerawork. She doesn’t showboat with any over-the-top camera shots; she just goes along naturally, presenting the manga to the reader with the variety of shots that most effectively tells the story.

And then with Fumiko Takano, it’s just her pure drawing ability. I realize that’s a pretty vague way of putting it. Her ability to express space is amazing. For example, when she draws concentration lines, they go off in a bunch of different directions. Basically, I just don’t get how she can make the reader feel the space so clearly without even drawing it in proper linear perspective. It’s not that she’s somehow faking her way through it or something, either — I feel like she’s managed to grasp something that isn’t a matter of technique, something fundamental.

The biggest thing, though, is her power of observation. Something that even acclaimed male artists can’t draw is the feeling of daily life, and that’s something Takano’s work has. Things that people do as they go on with their day — the poses that people make when they go to pick something up, for example, or when they eat, or when get up and go to the entranceway to put on their shoes, or when they stretch under a kotatsu. How is it that when she draws, say, amiddle-aged salaryman taking his shoes off at the office and putting his feet up on his coworker’s chair, or a man stretching out on his home sofa, she draws it with such an economy of lines, and yet you can actually smell the guy? She’s great with those little mannerisms. That power of observation. When people say a man is good at drawing, they’ll mean that he’s good at drawing people’s bodies accurately, or he’s good with spatial perspective, or his pictures look cool, and I can understand those skills sort of as extensions of my own skill set, but I haven’t really seen any male artists who can capture this feeling of life that I’m talking about. I guess if you include anime you could say that Miyazaki’s films really pay attention to that stuff, but for some reason you don’t ever see it in manga. I guess it’s not something male readers are looking for in manga. Honestly, I myself am absolutely terrible at it.

–Have you ever thought to try it?

Samura: Well, I have thought about it, but — and I know this’ll sound like an excuse — I’ve stayed far away from the sort of subject matter that calls for that level of portrayal of daily life. (laugh) My manga is pretty much always about flashiness, first and foremost.

–Like fighting?

Samura: Exactly. I’m thinking it might be time to start facing that daily life stuff more seriously, though.

Samura: I decided to do Ohikkoshi after stumbling upon Moyoko Anno and reading Happy Mania. I’d never seen a comedy like it before, and it made a real impact on me. I was actually trying to do something similar with Ohikkoshi, though I clearly failed somewhere along the way. (laugh)

–Samura does Happy Mania.

Samura: That’s what it was supposed to be. See, it’s always women who appear at the critical junctures in my life, leading me forward. Eventually I came to think of women as just plain better than me, which is why I always make the women in my manga into badasses, or really courageous, or indescribably beautiful. I always try to make the women mentally superior in my work. Do I have any manga where the men are superior? Hmm, I guess not. Even in Blade of the Immortal, the strongest is Makie.

–It does feel like the girls always come out on top in all of your manga.

Samura: I have this belief that you can’t kill off a woman without drama. If I’m going to kill off a female character, I need to make up an entire scenario to make it happen. Of course, I have no qualms about offing the men left, right and center, though. (laugh)

–It’s an interesting incongruity.

Samura: I can’t treat women as just plain background. I can’t portray them getting physically hurt past a certain point. Some artists don’t mind drawing women getting their heads blown open by bullets or getting sliced in half or whatever, but I don’t think I can do that. I simply can’t have them die ugly. I have that desire for them to be symbols of aesthetic beauty.

–No matter how much they may be bled and tortured…

Samura: I can’t let them lose their will or their beauty.

–In Bradherley they’re tortured in all sorts of ways, but they’re never made ugly.

Samura: Exactly. They’re made to hurt, up to a point for me…

–Up to the point where you can’t bear any more.

Samura: That’s right, where I can’t go any further. There’s an inner struggle, or like this mental barrier, and I just can’t do it. (laugh) But you know, as an artist, I think it’s great that there are people who can do that, and I know that it’s something I need to get over. So it’s not that I can’t do it because of some policy I’ve set for myself; it’s something I’m just unable mentally to do.

–When you draw women, do you have someone you use as a model for practice?

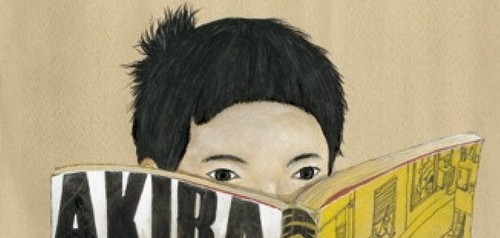

Samura: As far as manga character designs go, it’s probably male artists rather than female: Katsuhiro Otomo, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, and Yukinobu Hoshino, mostly.

–Three big-name masters.

Samura: Add those three together, divide by five, and you’ll maybe get my designs. (laugh) There are all sorts of other influences mixed in too, though. For drawing young girls, my favorite is model is Maretta, a character from Satomi Mikuriya’s Saketa Passport (“Torn Passport”). That’s pretty much where my ideal of what a heroine should be comes from.

–At what age did you read that?

Samura: When I was in university. The manga’s about a Japanese journalist in his thirties who goes to France, and there’s this 15-year-old French girl who comes on to him. Total fantasy. (laugh)

–Do they become lovers?

Samura: Well, she’s in love with him and they live together, anyway. It might be the root of my tendency to pair up middle-aged men and young girl characters. (laugh)

–He’s only in his thirties, so he’s not middle-aged. It’s just a man and a girl.

Samura: I guess you could say it’s pretty typical in stuff like Hollywood road movies. For me, I see that level of age gap as perfect for hitting that relationship sweet spot that stops just short of romantic love.

–The sweet spot for you stops just short of romance?

Samura: Yeah, because I can’t draw people who are seriously in love. (laugh) I mean, I wish I could. My goal since Blade of the Immortal ended has been to make a manga that has actual romantic scenes.

–This is a bit off-topic, but the men you draw have a sexiness to them.

Samura: I don’t really think too hard about the men. (laugh)

–So you’re not thinking at all about making them good-looking?

Samura: Hmm. Okay, well, my ideal male protagonist is Sword, the main character in Yukinobu Hoshino’s Bem-Hunter Sword, and I think he provided quite a bit of inspiration in Manji’s facial expressions. He’s like Cobra the Space Pirate, if Cobra wasn’t that strong. (laugh) He’s similar visually, and in terms of personality too, I think. I guess Manji’s a bit rougher around the edges. Honestly, I actually have a harder time figuring out how to do the pretty men.

–Was Anotsu in Blade of the Immortal difficult?

Samura: Yeah. Like, “What do I do with this guy?” (laugh) If I wasn’t careful, he could’ve turned out like Manji.

—Is it difficult maintaining his beauty as a man? It seems like you don’t have much trouble drawing the girls as beautiful.

Samura: Hmm, yeah. It was pretty hard for me to do this character who’s acting according to principle, like the nationalist activists from the Bakumatsu period. Even now, I’m still not used to it. I’m generally better at doing rough-and-tumble types, be they men or women. If I just make a manga naturally without thinking too hard about it, that’s what comes out.

–You’ve said before that you like Osamu Tezuka’s Shumari. It seems to me Manji bears some resemblance to Shumari, too.

Samura: He sort of does, doesn’t he. (laugh) He has that devil-may-care front, but then he’ll carry the load that’s his to bear. Also, in Shumari, the character I find captivating as a person is Yashichi, and I really want to do a manga with a character like him someday. He isn’t evil, he isn’t good; he’s driven by his own personal interest, but he’s not quite an antagonist. He’s not altogether cold-blooded – he may come off as devil-may-care, but he has his principles; he knowingly does some dirty things, but there’s a line that he never crosses. I want to do a character like that someday. ♦

Pingback: Feedly Friday: June 27, 2014 - Manga Connection

Thanks for the translation, I’m a big Samura fan!

Such insight. Thanks for translating!!

Pingback: Leaving Proof 245 | How Studio Proteus and Blade of the Immortal changed attitudes towards manga « The Geeksverse

Great interview! Thanks for translating, I really appreciate it.

Your translations are so quality. I return to this interview once in a while because it’s so damn wonderful (I was just quoting some parts of it to a friend lol). The way Samura views women is so unique and admirable. This is also insightful after having gone thru his Hitodenashi no Koi. He’s one of the few mangaka who portray the pain women feel so well that I feel like he really does appreciate women. Bradherley’s Coach was something I set down and picked up a couple of times because it was very difficult to finish. I thought I was desensitized to seeing rape in what I’ve watched or what I’ve read, but realize the mangaka and/or directors were just doing a shit job at portrayin it.

Thank you for sharing this. I’m a fan of Hiroaki Samura’s works. It is wonderful to know that he is such a thoughtful person. Well, I only had read two works though (Blade of Immortal and Ohikkoshi), sure I will read another soon.